Review: Juliane Noth, Transmedial Landscapes and Modern Chinese Painting (Harvard University Press, 2022)

Próspero Carbonell

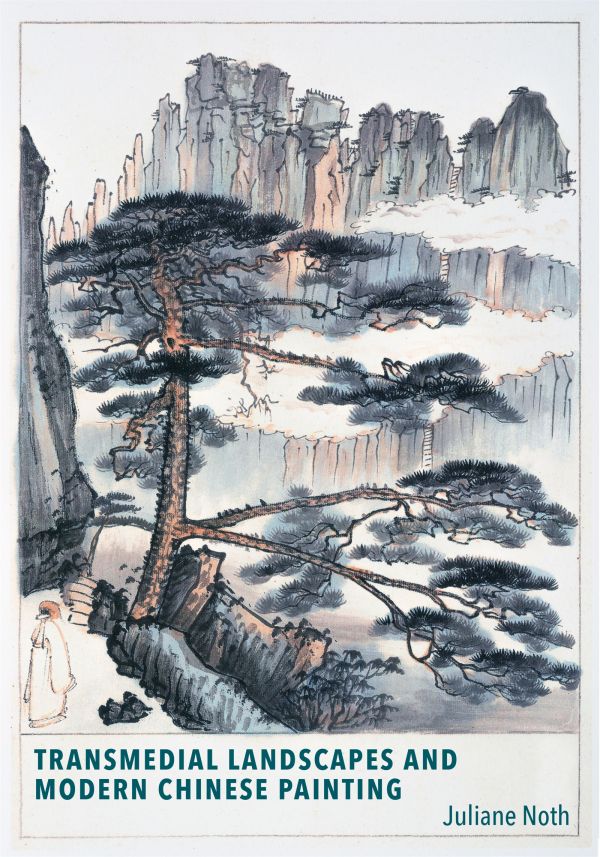

Transmedial Landscapes and Modern Chinese Painting by Juliane Noth offers a comprehensive exploration of the complexities of Chinese ink painting as it came into contact with modern media during the Nanjing decade (1927–1937). Organized into six chapters and enriched with historical maps, paintings, and photographs, the book embraces an interdisciplinary approach that bridges art history with transmedial analysis. Noth critically examines how shanshuihua (landscape painting in ink) was transformed into guohua, or “national painting,” challenging traditional narratives and introducing new perspectives on the integration of Chinese cultural identity with modern and Western practices. Through detailed analyses of artists such as Huang Binhong, He Tianjian, and Yu Jianhua, Noth not only illustrates how they navigated evolving cultural and political landscapes but also positions guohua at the forefront of global art discourses. This book challenges conventional views of Chinese art and underscores its role in shaping modern national identity, making it an indispensable resource for understanding the transmedial and transcultural currents that influenced China’s visual culture in the early twentieth century.

Noth, an East Asian art historian at Freie Universität Berlin, adeptly investigates the evolution of modern Chinese painting amid the political turbulence of the 1930s. Employing theoretical frameworks such as Irina Rajewsky’s intermediality and Lydia Liu’s translingual practice, Noth delves into the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary dimensions of Chinese art during the Nanjing decade. She explores the fusion of traditional techniques with modern media, including photography and printmaking, within the context of Western influences and nationalist initiatives like railway development, which transformed the relationship with the landscape by granting tourists and artists easier access to remarkable vistas and sacred sites. Her application of Thomas Mitchell’s concept of landscape agency elucidates how iconic locations in Southeastern China shaped artistic representation and configured a nationalist image that acknowledged its historical and spiritual depth. This is particularly evident in her analysis of the 1935 Zhejiang Provincial Exhibition, where she links social upheavals to shifts in visual culture that underscore national unity. Furthermore, Noth builds upon James Cahill’s theories on the evolution and spiritual and artistic significance of misty mountains such as Mount Huang, distinguishing her approach from the historical focus of scholars such as Michael Sullivan to offer a nuanced view of cultural exchange and artistic transformation.1 By illustrating how art journals and government-sponsored publications positioned guohua within a global discourse, Noth emphasizes their crucial role in projecting a progressive image of China that recognized its rich artistic legacy, while offering critical insights into now-missing artworks and highlighting the dynamic interplay between traditional aesthetics and modern visual media.

In her opening chapter Noth critically examines how the publication National Painting Monthly facilitated the integration of Western realism with shanshuihua, transforming landscape painting from an elite cultural symbol into a vibrant expression of national identity. She discusses the emergence of the “new Chinese painter,” a figure that skillfully blends literati ink techniques with contemporary artistic sensibilities, reflecting the journal’s crucial role in positioning modern Chinese art within a broader context. Subsequent chapters explore the transmedial strategies of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour, highlighting how artists like He Tianjian embraced outdoor sketching and nature drawing to sustain their connection to Chinese cultural identity while adopting new artistic perspectives facilitated by the governments inversion in transport infrastructure as well as the influence of Western art. Noth underscores the modernization of guohua through a detailed analysis of He’s The Fourth Cataract of the Five Cataracts in Zhuji (1934), which illustrates how direct engagement with nature enabled artists to adeptly navigate the complex interplay between past and present.

Additionally, Noth’s examination of dynamic interactions within influential publications, such as In Search of the Southeast (1934), demonstrates how the strategic juxtaposition of historical poetry, painting, and photography enriched modern Chinese art, reshaping its historiography by embedding it within a broader narrative of national identity formation and creative exploration.

In Chapters 4 and 5 Noth compellingly argues that Yu Jianhua masterfully integrated Chinese and Western traditions in his landscape compositions by emphasizing differences in perspective techniques. Preferring the fluid, encompassing view of shanshuihua over the fixed central perspective typical of Western art, Yu captures the spiritual essence of the landscape rather than its exact topographical complexion. Noth explains this synthesis through Yu’s travel albums, particularly Composition of a Complete View of the Five Cataracts (1934), where he merges premodern practices with modern photographic viewpoints, creating a visual collage that reflects both historical continuity and contemporary innovation. She further examines Yu’s use of handscroll and woodblock print formats, illustrating his seamless integration of diverse artistic methods, which both affirms his reverence for old masters and challenges the limitations of photography in capturing the complexity of such sites. Her analysis extends to Yu’s work featured in Liangyou (1935), where he used in situ drawings, photographic iconography, and printmaking to redefine Chinese identity through cultural symbolism and iconic landscapes such as Mount Huang and the famous Guest-Greeting Pine (1936). In contrast, she examines Lang Jingshan’s photograph Majestic Solitude (1934) to underscore the relationship between guohua and modern practices, showcasing how Jingshan manipulated photographic media to echo ancient Tang and the Northern Song artistic principles, thereby creating a unique visual narrative that blurs the lines between painting, photography, and the land. Noth contends that such artists navigated and shaped visual responses to socio-political challenges during the Second Sino-Japanese War, emphasizing their roles in transforming Chinese art historiography and revealing the tensions between locals and Japanese invaders.

Chapter 6 provides a nuanced analysis of Huang Binhong’s 1930s artworks, illustrating how traditional ink-wash techniques were combined with modern visual practices, such as photographic compositional strategies that introduced cropping, in contrast to the expansive compositions typical of literati painting. This synthesis not only showcases Huang’s personal engagement with Southeastern China’s geography but also captures the era’s sociopolitical tumult through dynamic brushwork and atmospheric effects enriched by printmaking aesthetics. Noth argues that Huang’s extensive travels significantly enriched his artistic vocabulary, merging direct observations with traditional motifs and new media, thereby transforming his portrayal of Mount Huang into a powerful national symbol during China’s rapid modernization. She further explores Huang’s theoretical writings, particularly The Essentials of Painting Method, highlighting how his integration of ancestral methods with modern innovation, that advocated for the relevance of Chinese art in nation-building. Ultimately, Noth posits that this transmedial interplay not only revitalized guohua but also redefined China’s national identity and cultural resilience amid Western influence.

While Noth’s book meticulously dissects the technical and intermedial aspects of modern Chinese landscape painting, it could benefit from a more sustained integration of external insights, such as Cahill’s account of melancholic reflection in Southern Song and Yuan landscapes.2 Such integration would deepen the exploration of tensions between longing for the past and embracing modernity, particularly in the works of artists like He Tianjian and Huang Binhong. Engaging more thoroughly with Chelsea Foxwell’s theories on nihonga and melancholy could add further nuances to Noth’s interpretations of emotional and cultural significances within modern guohua, enhancing her narrative of how these artists transformed Western methodologies to reflect East Asian traditions and socio-political contexts.3 Additionally, including a glossary of specialized terms would make the book more accessible to newcomers in the field, clarifying complex concepts and terminologies.

In conclusion, Transmedial Landscapes can be described as an essential resource that offers a compelling account of the merging of heritage and innovation in 1930s Chinese art. Through poignant examples like He’s Long Journey (1937), symbolizing broader national struggles, and the fusion of Chinese ink-wash painting with photographic techniques in Zhang Daqian’s Painterly Views of Mount Huang. Noth’s examination of Pan Yuliang and Hu Zhongying offers a nuanced analysis of how women artists integrated Western practices with Chinese aesthetics to challenge conventional gender norms and pioneer new avenues in the modernization of guohua, opening up pathways for further research on gender and modernity in visual studies in the early twentieth century. This book is indispensable for scholars and students alike, prompting a reevaluation of dominant narratives in art historiography.

- Michael Sullivan, The Arts of China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969). ↩︎

- James Cahill, The Lyric Journey: Poetic Painting in China and Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), 17. ↩︎

- Chelsea Foxwell, “The Painting of Sadness? Ends of Nihonga, Then and Now,” ART Margins 4, no. 1 (2015): 27. ↩︎